This blog comes with a flimsy pretext.

Prompted by the imminent appearance of the writer Joanna Walsh on tomorrow night's A Leap in the Dark, I dug up this unpublished blog about the novel on which Alfred Hitchcock based his great film Vertigo. Because Joanna wrote a novel with the same title. Vertigo, I mean. So, come to that, did W. G. Sebald. But he's not a guest on A Leap in the Dark.

Joanna will be in conversation with Emma Warnock of the Belfast-based No Alibis Press, about her forthcoming novel Seed. Invitees will receive an exclusive extract and introductory note from Joanna in the morning.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Prompted by the imminent appearance of the writer Joanna Walsh on tomorrow night's A Leap in the Dark, I dug up this unpublished blog about the novel on which Alfred Hitchcock based his great film Vertigo. Because Joanna wrote a novel with the same title. Vertigo, I mean. So, come to that, did W. G. Sebald. But he's not a guest on A Leap in the Dark.

Joanna will be in conversation with Emma Warnock of the Belfast-based No Alibis Press, about her forthcoming novel Seed. Invitees will receive an exclusive extract and introductory note from Joanna in the morning.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

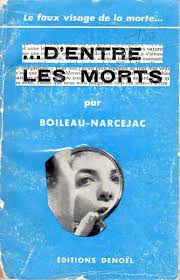

D'entre les Morts is a modestly competent psychological thriller by the French writing duo known as Boileau-Narcejac, first published in 1954. It's fair to say that it would attract little attention today had it not formed the basis of Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. The novel was recently republished in English, and I was delighted to be given the chance to review it, because the film has been a personal obsession since I saw a faded print screened in a Manchester flea-pit nearly forty years ago. After multiple viewings it remains as fresh and complex and alluring as ever, one of a handful of films that deserve and repay close attention over decades. It is an undisputed masterpiece, although on its release in 1958 the director's forty-fifth feature met with a lukewarm reception and would not appear in the Sight & Sound critics' poll until 1982, when it came seventh. In the most recent poll it was voted the greatest film of all time, displacing Citizen Kane, which had occupied the top spot since the poll began fifty years ago. Such lists count for little, but if pushed I'd argue that Hitchcock is a greater director than Orson Welles while Welles is the greater artist. This is the kind of distinction that used to prompt heated exchanges in the bar of the old National Film Theatre, spiritual home to many a passionate cineaste.

Reading the novel, one experiences (as I note in my TLS review) an unnerving sense of déjà lu, because although the setting is Paris and Marseilles before and after the German Occupation, the premiss is immediately familiar: a wealthy industrialist employs an ex-cop to keep an eye on his troubled wife, Madeleine, who appears to be possessed by the spirit of a dead ancestor. The cop soon becomes infatuated with her, attracted by her chilly glamour and aura of sadness, and when he witnesses her apparent suicide he becomes a melancholy, deracinated alcoholic. He later encounters another woman, appropriately named Renée, who appears to be Madeleine's double, her reincarnation. He attempts obsessively to re-make her in the image of his dead lover, scrupulously selecting her outfits, jewellery, make-up and hair (women's hair is a recurring motif in Hitchcock's oeuvre).

Vertigo is an intensely romantic film, but also profoundly morbid. There's a whiff of necrophilia in the movie, and considerably more than a whiff in the novel, where even Madeleine's perfume, Chanel No. 3, is headily redolent of “fresh earth and wilting flowers”. The besotted cop single-mindedly pursues his fantasy, described bluntly by Hitchcock in an interview with François Truffaut thus: “He wants to sleep with a dead woman”.

The director's perverse genius extended beyond a transgressive modern take on the Eurydice myth to explore themes of power and freedom; the power of men over women, of human beings over their fate and our dreams of freedom from death. Hitchcock wasn't especially interested in the mechanics of plotting, and audaciously gave the secret away thirty minutes before the end of the film in a combination of flashback and voiceover. What interested him – and what makes the film a timeless pleasure – is the human dilemma, the dreamy mutability of Kim Novak, who delivers one of cinema's greatest performances.

Later in the Truffaut interview Hitchcock also said: “Some films are a slice of life. Mine are a slice of cake”. Surely what he intended to say – and quite possibly said, using an idiom lost in translation – was: “Some films are a slice of life. Mine are a piece of cake”. This casual dismissal of his astonishing virtuosity served to deflect attention from the private obsessions and fears that he smuggled on to the screen, for a popular audience hungry for distraction, sensation and entertainment.

No comments:

Post a Comment